William P. Clark Oral History

[…]

Knott:

You mentioned Suriname in your answer. Are you willing to talk a little more about what happened in Suriname?

Clark:

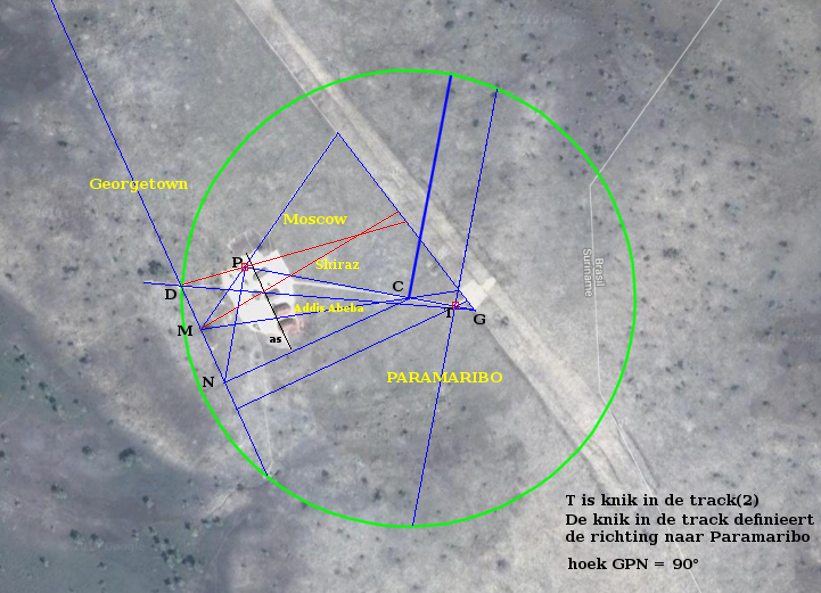

Yes. We had intelligence requiring, we felt, some immediate action regarding this little Caribbean country on the north shore of South America of 250,000 people as I recall.[Desi] Bouterse, a treacherous person, who like Sergeant [Samuel] Doe liked to line up his Cabinet and shoot them occasionally, was in direct communication with [Muammar] Gaddafi and Cuban intelligence directorates. It was once known as Dutch Guiana. The Netherlands had an interest in it, a paternal and economic one, even though they’d pulled out, leaving Bouterse to his own ends. But we had intelligence that planes were actually loaded in Libya with arms and communications gear prepared to go to Paramaribo and set it up as a new Cuba.

The Soviets had planned and were prepared to open an embassy, the only embassy as far as I can recall, on the South American continent. The President determined among a very small group—Shultz, Weinberger, Clark, and Don Regan, the latter who happened in accidentally to one of our conferences—a daring plan. It was a war plan, a false one but looking very real on paper, by which, as the President said, “the great colossus of the north” would invade Suriname to stop all of this, including a parachute drop and Weinberger’s ships sailing in. So with that information, John Poindexter, General [Paul] Gorman, I forget who from the agency, and I got into a plane at Andrews Air Force Base in the hangar, late at night, having made appointments with the Presidents of Venezuela and of Brazil to ask to meet with them or their representatives three days hence. We considered this an emergency situation to stop a new Soviet foothold in our front yard, giving the Soviets a chokehold on the mouth of the Caribbean.

So we flew into Venezuela and met with the President. Our message was, “Look, either you take care of the situation, of the Soviet foothold, the Cuban foothold—” Cuba was behind it. [Fidel] Castro’s number one intelligence director had orchestrated all of this. “Either you take care of it down here or we’ll have no alternative but to do so ourselves,” and then laid out our war plans in front of them. He turned pale, and before I left his office said, “Talk to Brazil, they’re closer. I don’t want anything to do with it right now, I’m in enough political trouble.”

So we flew into Brasilia, not to meet with the President but his Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and military leaders. We parked at the end of the runway, it was after dark. As John Poindexter reminded me, upon perceiving the air drop and the Navy coming in, the Chairman ran to the men’s room and threw up, he was so frightened. But the long and the short of it, our approach worked and Brazil moved in with a carrot and stick to Bouterse with social programs and stopped the Soviet incursion into Paramaribo. As far as I know, they still don’t have a Soviet representative there. So our plan worked. If it hadn’t succeeded, I’m sure we would have been called up before some Senate committee to explain why we would have attempted such a foolish thing.

Knott:

So this was one instance where secrecy was maintained.

Clark:

Absolutely and necessarily at the President’s order.

Knott:

I don’t think it’s ever been—

Clark:

Absolutely. Secrecy was maintained—from the Netherlands press there were several stories touching on it, but no one has really pressed it. When I returned to Washington, my staff met me saying, “Where in the world have you been? You’re in trouble.” I said, “What do you mean?” They said, “Well, the Baker group feels that you’re off starting World War III and you took Air Force One.” The President insisted that we take not number two or three but the plane that we took. I’d forgotten which one it was, but in any case Jim was in charge of all White house aircraft. We hadn’t asked his permission because the President told us that we weren’t to discuss this project, if it could be called that, with anyone other than those in the room. Oh, by the way, I missed mentioning Casey earlier. He was obviously involved in this.

Knott:

Was he on this trip that you referred to?

Clark:

No, Dewey Clarridge came along, that being his region for the agency. Anyway, the networks had that Sunday aired the fact that I was away on a mission without authority, that the White House had lost confidence in the National Security Advisor for doing things out on his own. Lesley Stahl, I recall, let it out early, I saw a rerun of it. So I had to assure our own staff people, who didn’t know about the project, that as far as I knew I still had a job. It all died down and went away in a day or two. But it was an interesting little project. We were gone actually just two and a half days on the weekend.

[…]

[Samual Doe was een Liberiaanse sergeant, die in April 1980 een coup pleegde in Liberia, waarbij leden van de toen zittende regering werden geexecuteerd.]